Consistency training IV: Beyond invariance

In Consistency training II: How does it work? we got perfect accuracy on our classification task using consistency training and a handful of labels. But we don’t actually need those labels. If we’re willing to get creative with how we scrape together a supervisory signal then we can solve simple tasks with no labels at all.

As we covered in the intro, consistency training exercises a form of supervision. It allows us to communicate with the model not through labels but through the specification of constraints. In most work on consistency training that means enforcing invariance across commonly used data augmentations. But invariance is only one type of consistency. If we can come up with enough constraints to fully bound the behavior we want, the model will be left with no choice but to solve the task.

Look ma, no labels! Solving a simple imitation learning task using only consistency training and output shaping. We can specify constraints so restrictive that they effectively mimic labels in the supervised setting, collapsing all information not relevant to our downstream task. Lane-following is the only option.

Output shaping

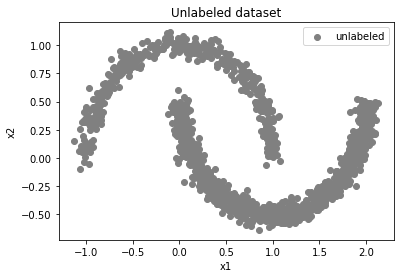

Let’s return to our toy dataset from part II to show how output shaping and consistency training can solve an even simpler task than the lane-follower above: halfmoons classification. The code for this example is at this Colab.

Like last time, the data team gave a dataset that we know is composed of two classes, bananas and plums. But this time they won’t be able to give us any labels.

A completely unlabeled dataset that we know is composed of two classes: bananas and plums.

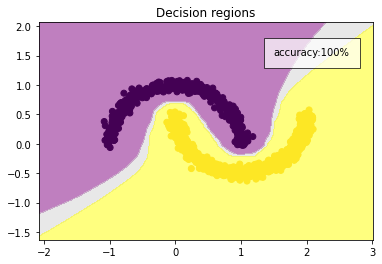

We may not have labels but we can at least narrow down the hypothesis space of possible decision boundaries by doing the same consistency training as before. We’ll do a simple MSE on our features to enforce consistency across views. The model is looking for a needle in a haystack and we’re able to make the haystack a lot smaller with our invariance constraint—if decision boundaries can’t cross our clusters, there are only a few places they can go.

########################

# Consistency loss

########################

# Stopgrad on one lane for stability

with torch.no_grad():

_, features_1 = model(x)

# Data aug and gradients on the other lane

pred, features_2 = model(aug(x))

consistency_loss = mse(features_1, features_2)We’ve made the model’s job a lot easier, but we’ll need a bit more information to make a classifier. The data team may not have given us any labels, but they did mention the dataset is probably around 70% bananas 30% plums. We can use that. This constraint will narrow the hypothesis space enough to fully solve the task, even without labels.

########################

# Output shaping loss

########################

# Rough estimates of std and class breakdown are fine.

target_std = .8

target_class_percentages = torch.FloatTensor([.3, .7])

output_shaping_loss = mse(target_class_percentages, pred.mean(0)) +

mse(target_std, pred.std(0).mean())

loss = consistency_loss + output_shaping_lossThat’ll do it! Like last time, the consistency training will create contiguous zones, neither of which will admit the decision boundary. Adding the additional constraint of a 70-30 split is the coup de grace: the model will have no choice but to place the decision boundary where we want it.

Consistency training + output constraint is enough to create a perfect classifier.

Beyond invariance

In all the work we’ve done so far—and in all the literature we’ve reviewed—consistency always means invariance across views. But consistency doesn’t have to mean just invariance. We can also think about it more broadly as maintaining self-consistent behavior across views.

Sometimes that means behaving in the same way (i.e. invariance) but sometimes it means giving an opposite response, or double the response, or five minus the response, or whatever. If we’re predicting steering in an end-to-end self-driving car, for example, then the model shouldn’t be invariant to a horizontal flip—it should output the exact opposite command. An object detection model probably shouldn’t be invariant to crop or rotation, its bounding boxes should shift correspondingly with the transformation.

Getting specific

How we define self-consistency is dependent on the downstream task we have in mind. The more downstream tasks you try to satisfy with your features, the fewer constraints you can impose. The fewer constraints you have, the more parameters, compute and data you need for a given level of performance on any given task. Supervised learning creates such powerful features with such relatively little data precisely because it collapses so much information. A hotdog detector is easier to train than a hotdog brand detector.

Those of us without 512-GPU pods and billion-sized image datasets should probably focus on learning narrow, task-specific features rather than universal, holy-grail features that work on every downstream task. ^ Yannic Kilcher calls these holy-grail features Eierlegende Wollmilchsau—which is German for ‘a pig that lays eggs, gives milk and produces wool before it’s turned into a tasty Sunday roast.’ We should try and put together a set of constraints so strict that they mimic the supervisory signal we would have gotten from task labels. “Unsupervised” doesn’t have to mean “general”, it can be totally bespoke.

Learning a lane follower

Let’s apply this “bespoke over general” approach to a more difficult toy problem: lane-following. We have unlabeled expert trajectories from our miniature car simulator. If we had labels, we’d just do behavioral cloning on them. Consistency constraints and output shaping, however, are enough to solve the task even without labels. A small set of constraints will do the trick:

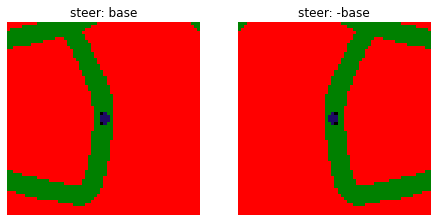

Horizontal flip. We know that if we flip the image, the model should output the exact opposite steering command.

Horizontal flip should give opposite steering command.

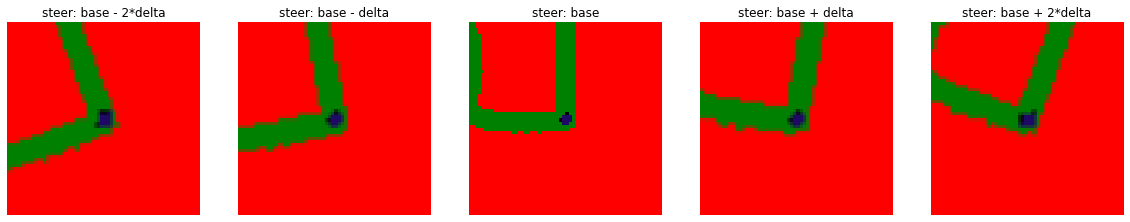

Correction consistency. If we nudge the camera to make the car think it’s veering, it will respond with a correction. If we nudge the camera by the same amount in the opposite direction it should respond with the same magnitude of correction but in the opposite direction. If we nudge it twice as hard, it should respond with twice the correction. We simulate “nudging the camera” by rotating the image.

Corrections to different camera perturbations should be self-consistent. We don’t know what any of these actual steer commands are, we just know they need to be consistent with eachother.

Output shaping contraint. The constraints above are enough to get the shape of the data but not the scale or shift. The model could satisfy the rotation and flip constraints with really huge or really small turn commands, all of them nicely scaled relative to each other but not calibrated to the outside world. To enforce scale, we can estimate the std of the steering commands. ^ Is this cheating? Hell yea. We have to estimate this from real data like in the halfmoon example above. But it’s totally legit to think we can get a rough estimate of these numbers from the data team. Applied ML is a street fight, take anything you can get! We can also add zero mean as a constraint for stability, though the flip constraint above also encourages this.

And that’s enough! With those constraints in place we’ve left the model with no choice but to create a decent lane follower.

As a final note, our “differently supervised” model learns the same features as a normally-supervised model. We’ve managed to communicate the same information to the model as we would have with labels, but using a different set of supervisory signals.

Showing what the model “sees” using the integrated-gradients approach. This is the same pattern of activations as a supervised model. The agent isn’t perfect—it cuts corners and totally loses the lane at the end.

Previous post: Consistency training III: An engineer’s guide to the literature